gh the trees in northeastern Oklahoma.

gh the trees in northeastern Oklahoma. Or, maybe it began when a miner, heading home just after dark, got lost in the woods. Some say that his wife, fearing the worst, grabbed an old lantern and set out to look for him, wandering until dawn. When her husband failed to return a second night, she set out again, and from that point on, each night, until she died. Now her ghost, carrying that lantern, searches for her husband.

Some say her lantern is the light that the Quapaw girl saw. Others suggest that the light was already there when the first of the white man arrived in the area around the beginning of the nineteenth century. Some thought it might have actually appeared about the time of Christ, but there were no humans around the area two thousand years ago. At least none who left a record for us to find.

Whatever the source of the light, or origin of the legend, the light is still there. I know because I have seen it. It appeared on each of the nights I was there, showing up about dusk and flashing around the sky until we left four or five hours later. Given what I know, I suspect it stayed until dawn and then gradually faded into the brightness of the day.

I spent a week in Joplin with Monty Skelton who, at one time, was the president of the North American UFO Organization. That first night, in the mid-1970s, as we pulled up near the somewhat dilapidated Spooklight Museum, about dusk, the light twinkled into existence hovering down the road. As Skelton stopped the car, I pulled my camera from the back, set up the tripod, and began to shoot. I hadn’t expected to see anything and hadn’t been fully prepared. I had only part of a roll of film.

Garland Middleton, who owned the museum in the 1970s, told me later that night, "I’ve seen a lot of people try to take pictures, but none of them got anything."

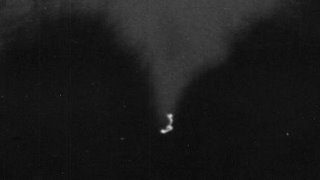

I finished the roll of film and the Spooklight was still there. Using binoculars, I watched it bob and weave, seeming to be about a hundred feet above the ground. It broke into three parts, and then five, and finally vanished for several seconds. Moments later it burst out again, outshining everything around it.

When it was totally dark, the outside lights of the museum had been turned on and I could see Middleton’s car, the door labeled "Spooklight," sitting close to it. While others stood on the road watching the light, and other cars arrived and left, I walked over to the museum.

Middleton was sitting on a couch by an old wood burning stove. He had worked with the original owner, Meadows, had run the museum for him, opening it in morning and sometimes closing it at night.

Meadows had been estranged from his own family telling Ron Bogue of the Joplin Globe, "I’ve got three sons. One of them I haven’t seen in twenty years. I don’t know where he is. My other two boys live in Kansas but they never come to see me... I don’t know them." Middleton, who shared a love of the Spooklight became, to some extent, Meadows’s heir, replacing the family who had no time for him.

When Meadows died, Middleton took over the museum, living out on what Meadows had called "Spooklight Corner." In the mid-seventies, there were two pool tables and three pinball machines in the museum. On one wall there were dozens of clippings about the light, several photographs of it and a short story about the museum. I read the clippings which told me little about the light and a lot about the legends including one that said river boat passengers had sometimes reported the light. Today I’m not sure what river boats the writer meant, or even what river the boats would have been traveling.

I studied the photographs which suggested that Middleton might have been exaggerating when he said that no one had much luck taking pictures. He was even selling post cards that had picture of the light on the front. It was apparently one of many taken by Meadows who had been a photographer in his younger years.

In the mid-1970s, Middleton was an old man, fairly tall and very thin. He was friendly and eager to talk about the light. He told me, "I first seen the light forty-years ago. It looks the same today as it did then. Now it usually stays away but it used to come right down the road, almost to the corner."

Middleton, like so many of the others I talked to, told of friends who had been within twenty feet of the light. He said that he had once gotten to within fifteen feet, but that was years ago. "Nowadays it seems to stay away more. It doesn’t come very close but it’s always out there."

There were a couple of teenagers in the museum. I asked these young men, who were playing pool, if they had seen the light. The taller of the two, who had slightly reddish hair and couldn’t have been more than eighteen said that he hadn’t really seen it and didn’t care to. He was just there to play pool. The other, shorter, stockier kid said that he had seen it but he wasn’t all that interested in it now. Pinball and pool had drawn him, and his friend, out to the museum. They could play uninterrupted because rarely anyone else came in to play pool.

Back outside, I traveled up the road where the Spooklight floated but when I reached the top of the last hill, the light vanished. Below me, stretched for miles, was part of Oklahoma. In the distance I could see lights flickering along a stretch of highway and some of them looked remarkably like the Spooklight but everyone said they weren’t.

"Besides," said James Smith of Joplin, "the light was here long before the town or cars or electricity."

Well, maybe.

We turned around and started back to the museum. In the rearview mirror we could catch glimpses of the light still hovering over the hilltops, seeming to pulsate and change color.

Although we tried to drive up on it several times, we always failed. One man volunteered that he sometimes came in from another dir

ection, using some of the back roads and that way he could "fool it." Once, as he turned onto "Spooklight Road" it had passed over his car. At least that is what he said.

ection, using some of the back roads and that way he could "fool it." Once, as he turned onto "Spooklight Road" it had passed over his car. At least that is what he said.He wasn’t alone in making such a claim. Others said that they had friends, family, cousins, or had just heard that the light sometimes came down the road. One man said that his brother reported that the Spooklight had touched the hood of his car, sitting on it for several seconds before disappearing. When I traced the brother, he said, no, that had been a friend. But then the friend related that he had heard it from someone else. The story had evolved into the old "friend of a friend" routine. I could never get to the original source.

I returned on a couple of other nights. Once I was there with Marta Poyner, a reporter for the Joplin Globe. She said that she had been out several times but had never seen the Spooklight. Just as we pulled up, it flared once and seemed to split into pieces. I pointed it out and she said, "Oh, I’ve seen that before. I always thought it was car headligh

ts."

ts."One of those who had driven out that night overheard her comment and said, "It’s been here since 1811, long before there were any cars."

Well, maybe.

We both took pictures, and just like the batch I had taken the first night, these too, came out, contrary to the legend. Once we had finished, we tried walking down the road to the light, but after a mile or so, we gave up. The light wasn’t any closer, and I had already tried to approach it in a car.

Back at the museum, I ran into John Wysong, a long time Joplin resident. He was with his wife and son, and though he had first seen the light in 1955, he returned two or three times a year to look at it.

James Wysong, the son, had also seen the light before, but his wife, from Arizona had not. She hadn’t even heard of the light until after she was married into the Wysong clan.

I asked her what she thought of it. She said, "I didn’t know what they were talking about. I really didn’t believe that I would see it but there it is. I don’t know what to make of it but I know there must be some kind of explanation for it."

The younger Wysong said that he had tried to find out exactly what it was. One night he had tried to stalk it, but after only a few minutes had given up. He didn’t say it, but seemed to imply he didn’t really want to get too close to it. He didn’t know what he might discover and that had concerned him.

The older Mrs. Wysong leaned across the front seat of the van and said, "After studying it all these years, you would think that someone would be able to figure it out what it is. It’s a real mystery to me."

Well, she was right. You would think that after all the studies someone would have a logical explanation for the Spooklight.

During the Second World War, the Army Corps of Engineers spent some time studying the Spooklight. Colonel Dennis E. McCunniff was interviewed in his headquarters at Camp Crowder and said, "I know that no one is going to like this, or even believe this, but we found a few interesting things about the Spooklight. We discovered that it is seen more frequently in the winter but I believe that is due to the lack of foliage. Leaves off the trees and that kind of thing. After looking at it, we’ve determined that it’s a refraction of light. An optical illusion."

Well, maybe.

In 1960, William K. Underwood, a high school student from Carthage, Missouri, spent 400 hours studying the light for his high school science project. He claimed that the lights were from a section of highway going east out of Quapaw, Oklahoma, and directly west of the road where the Spooklight is seen. Underwood, with the help of his friends and family, designed a number of experiments to prove his theory. Using a spectroscopic photograph, Underwood discovered that the light was from an incandescent source. In other words, the light came from car headlights. This seems to corroborate the theory given by Colonel McCunniff.

He also had friends drive down the stretch of highway, some with colored filters on their headlights. He watched as they flashed signals at him that were reflected in the Spooklight, verifying, to some degree his theory.

Others, equipped with mirrors, binoculars and cameras made similar experiments. Given that the signals were flashed in random patterns so tha

t those at the museum didn’t know exactly when they were coming or what the signals would be, it provided some dynamic evidence.

t those at the museum didn’t know exactly when they were coming or what the signals would be, it provided some dynamic evidence.A Joplin resident, who didn’t want to be named, said that he believed the Spooklight to be some kind of magnetic aberration that caused an ionization of the atmosphere near it. That caused the gases to glow and could account for the reports that the light had been attracted to cars. The gases would have one electrical charge and the car would have the opposite. The problem was that the glow lasted for hours and that suggested it wasn’t an ionization. Besides, there was no real mechanism in the explanation to cause the glow. The air might be ionized, but that, in and of itself, does not cause it to glow.

Spooky Meadows, in 1969, told Bogue of the Globe that he had formed his own opinion of what, according to Bogue, "has baffled everyone from Army Engineers down to amateur scientists." Meadows said, "It’s a light, of course. But the mystery is - what causes it?"

Most of those who live in Joplin will tell those who ask that there is no good explanation for the Spooklight. They will tell you that the Army studied it, as have scientists and investigators, but no one has explained it. They will tell you that it is probably some kind of a natural phenomenon, but they will refuse to identify exactly what that phenomenon is, preferring to sound somewhat skeptical while denying any and all explanations.

They will also mention, whenever an explanation is offered, that the light was there long before cars and electricity arrived on the scene. I could find no documentation to support that. The first of the newspaper articles and other documents are from the beginning of the twentieth century.

Those who live in Joplin are going to believe what they want to believe and they won’t listen to an outsider with an explanation. That attitude was typified on a call-in radio program originating in Joplin. One woman heard that we were there and wondered why we didn’t just stay home. The light wasn’t ours to study, but it was theirs. It belonged to Joplin. "If they want to study something, why don’t they do it at home and leave us alone," she said.